Amplifying a Griot’s Voice

The night the exhibition Container/Contained: Phil Freelon – Design Strategies for Telling African American Stories opened at the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture, Sierra Grant stood before a crowd of more than 200 visitors and read the words of the late Civil Rights leader John Lewis. The moment was meaningful for several reasons.

First, it marked the culmination of two years of work by Grant and a team of fellow UNC Charlotte architecture students, under the direction of architecture faculty Emily Makaš and Greg Snyder, to develop, design, and install the exhibition at the Gantt Center honoring the acclaimed North Carolina architect Phil Freelon. Second, Grant (pictured right) was standing in the soaring atrium of a building designed by Freelon and named for another celebrated North Carolina architect and statesman, who was in the audience that night.

First, it marked the culmination of two years of work by Grant and a team of fellow UNC Charlotte architecture students, under the direction of architecture faculty Emily Makaš and Greg Snyder, to develop, design, and install the exhibition at the Gantt Center honoring the acclaimed North Carolina architect Phil Freelon. Second, Grant (pictured right) was standing in the soaring atrium of a building designed by Freelon and named for another celebrated North Carolina architect and statesman, who was in the audience that night.

It was also a moment of courage for Grant, who is usually reluctant to speak in public, but who, Makaš said, deserved to be “front and center.” And perhaps above all, it was important that when she read Lewis’s words – “Phil Freelon was an artist, an architect, and a griot who immortalized our culture in steel, glass, and stone” – Lewis’s and Freelon’s culture was her culture, too.

“Actually reading the passage was terrifying,” Grant said the day after the exhibition-opening reception. “There were so many people at the opening, and I didn’t want to mess up such a beautiful quote. But, after working tirelessly on this project for the past two years, it was an honor to read John Lewis’s thoughtful words about Freelon, because they really embodied what the Container/Contained exhibition is about and really helped to shed light on why it is so important to us to pay tribute to Freelon’s art, architecture and life overall.”

Creating something real

Grant, who received a B.A. in Architecture in 2021 and is now a graduate student in the Master of Architecture program, was one of 22 students who joined Makaš and Snyder to create the exhibition. An associate professor of architectural history and the associate director of the School of Architecture, Makaš had involved students in exhibition work before. In 2019, a class she taught created the Legacy of Lynching exhibition at the Levine Museum of the New South, and the semester-long experience was rewarding for her and for the students who participated.

That same year, Freelon died from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, cutting short a tremendous architectural career that included, in addition to the Gantt Center, the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta, the Museum of the African Diaspora in San Francisco, Emancipation Park in Houston, the Motown Museum in Detroit, and the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

Architect and former Charlotte mayor Harvey B. Gantt in the Container/Contained exhibition at the Gantt Center. Photo by Ortega Gaines.

Architect and former Charlotte mayor Harvey B. Gantt in the Container/Contained exhibition at the Gantt Center. Photo by Ortega Gaines.

Makaš decided to build upon her decades of research into the topic of identity and the built environment and investigate Freelon’s masterful ability to design buildings that embody and evoke African American history and culture. And she knew she wanted to bring students into the research project.

“I’m a teacher, and it was a project that’s much bigger than one person,” she said. “The students bring so much to it and have so many great ideas, and they don’t tend to have the chance to create something real.”

Artist, architect and griot

Creating something real was a big attraction for Grant.

“Being in the School of Architecture is very exciting, but nothing we design ever gets built. So, designing the graphics for the Freelon exhibition appealed to me not only because Phil Freelon was an amazing artist, teacher, and architect, but because we are getting to create something for people to actually visit and experience.”

Like Grant, fourth-year architecture student Tahlya Mock spent the better part of two years assisting Makaš, researching and writing the text that Grant would incorporate into the panels she designed. Mock watched and read interviews with Freelon, studied newspaper and magazine articles about his work, analyzed images and even traveled to cities like Durham, where Freelon lived, to see examples of his buildings.

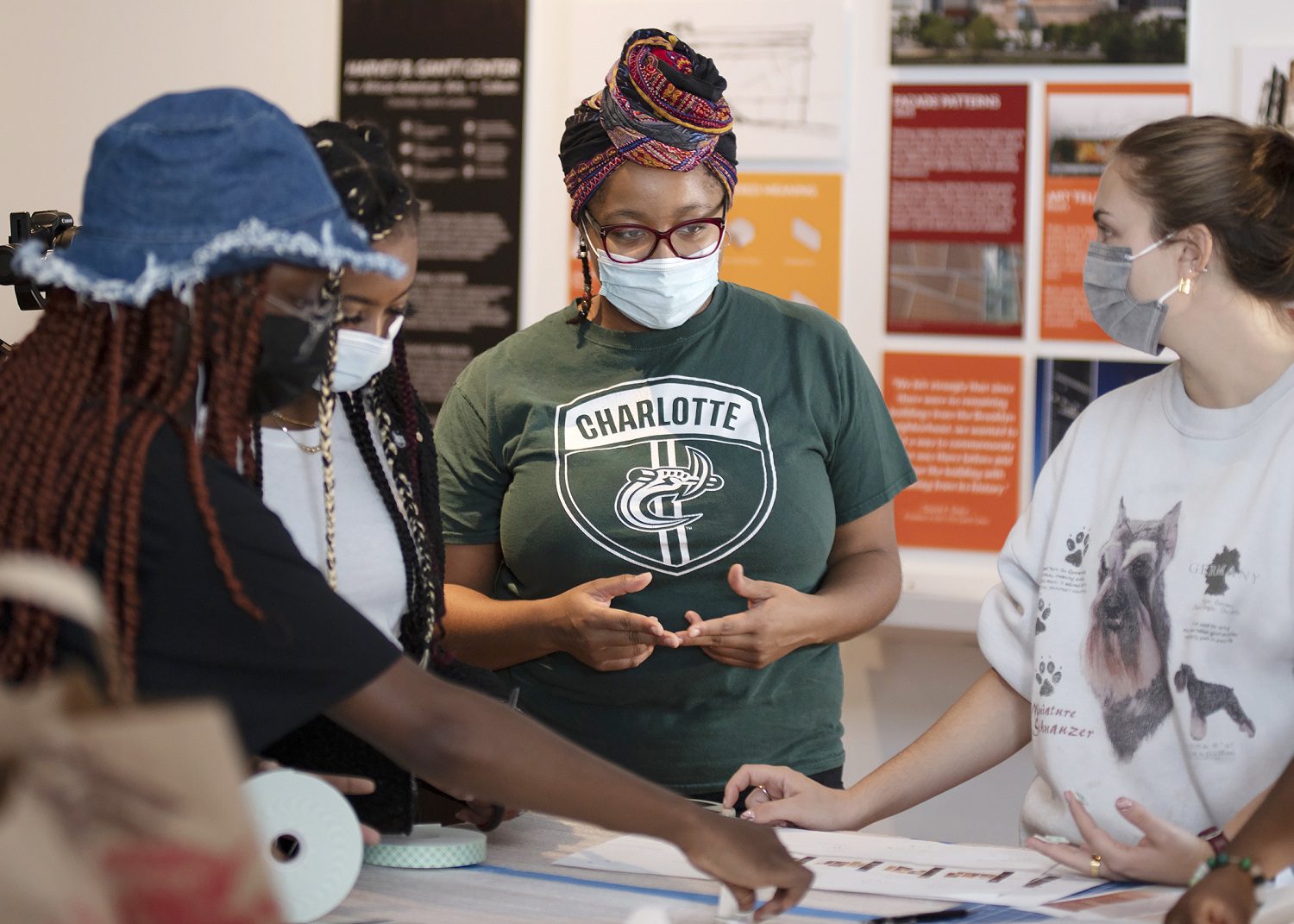

Tahlya Mock (center) and fellow architecture students during the installation of the exhibition at the Gantt Center. Photo by Wade Bruton.

Tahlya Mock (center) and fellow architecture students during the installation of the exhibition at the Gantt Center. Photo by Wade Bruton.

“Before being an architecture student, I didn’t have any Black architects to look up to,” said Mock, who grew up in Arkansas and Kentucky. “I think it’s really progressive of the School to fund and organize a project like this. I think it’s important for Charlotte and important for North Carolina. And since it’s an exhibition, it can travel. It could go to Atlanta, to Baltimore, to D.C. It has the potential to reach so many people.”

After the Gantt Center closes the exhibition in January, it will travel to Raleigh, where it will open at the North Carolina Museum of Art in February and be on view this spring to coincide with the expected completion of Freelon’s North Carolina Freedom Park in downtown Raleigh. From there, the team hopes it might move to other cities that host Freelon’s work.

Culture immortalized in steel, glass and stone

The exhibition presents Freelon’s design strategies in 10 projects, exploring how the appearance of the building – the way it is laid out, how it situates in the landscape, the colors used, the patterns on the façade – reflects specific ideas and connects to both contemporary and historical communities.

“What’s so cool about all of Freelon’s work is you can look at these projects and understand the concepts so easily,” said architecture student and Levine Scholar Quinton Frederick. “He takes a simple, really powerful idea and makes really beautiful architecture with it. But when you try to make a model of it, it’s so complicated. There are so many nuances.”

Quinton Frederick (left) with professors Emily Makaš and Greg Snyder during the installation at the Gantt Center. Photo by Wade Bruton.

With Associate Professor of Architecture Greg Snyder as their mentor, Frederick and other architecture students designed and 3D printed small models of a half-dozen of Freelon’s buildings, which are displayed on special lighted shelves that Snyder created for the exhibition. Like the 199 wall panels of text, diagrams and images, the models demonstrate how concepts take shape in Freelon’s designs.

“Greg has been really awesome to work under,” Frederick said. “He has such expertise. With the pandemic, I hadn’t made any models since freshman year.”

Frederick was assigned the Gantt Center and Smithsonian Museum models – nine pieces in all.

“The two model projects I did are really mine, and to have something I did in a museum is really awesome.”

Models of the Harvey B. Gantt Center, created by Quinton Frederick for the exhibition. Photo by Ortega Gaines.

Models of the Harvey B. Gantt Center, created by Quinton Frederick for the exhibition. Photo by Ortega Gaines.

That enthusiasm and sense of ownership were especially evident, Makaš said, during the week before the exhibition opened at the Gantt Center, when students showed up day after day to hang boards and place models and correct last-minute mistakes.

“I was just so impressed. They were so eager and helpful and excited to be part of it.”

They came, too, to the grand opening – almost all 22 of them – and watched with pride as visitors moved through the gallery, reading their panels and admiring their models.

“I know it’s Emily’s exhibition,” Mock said, “but I kind of feel like it’s mine, too.”

The UNC Charlotte student team with professors Makaš and Snyder at the opening reception for Container/Contained. Photo by Ortega Gaines.

The UNC Charlotte student team with professors Makaš and Snyder at the opening reception for Container/Contained. Photo by Ortega Gaines.

Get a behind-the-scenes glimpse of the installation process in this 49-second video.