Exhibition Showcases an Emerging Architectural Revolution

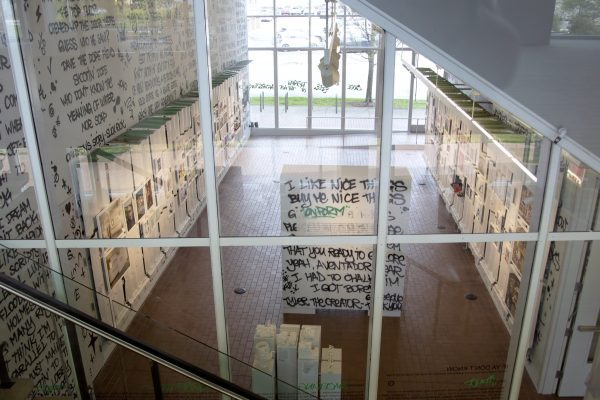

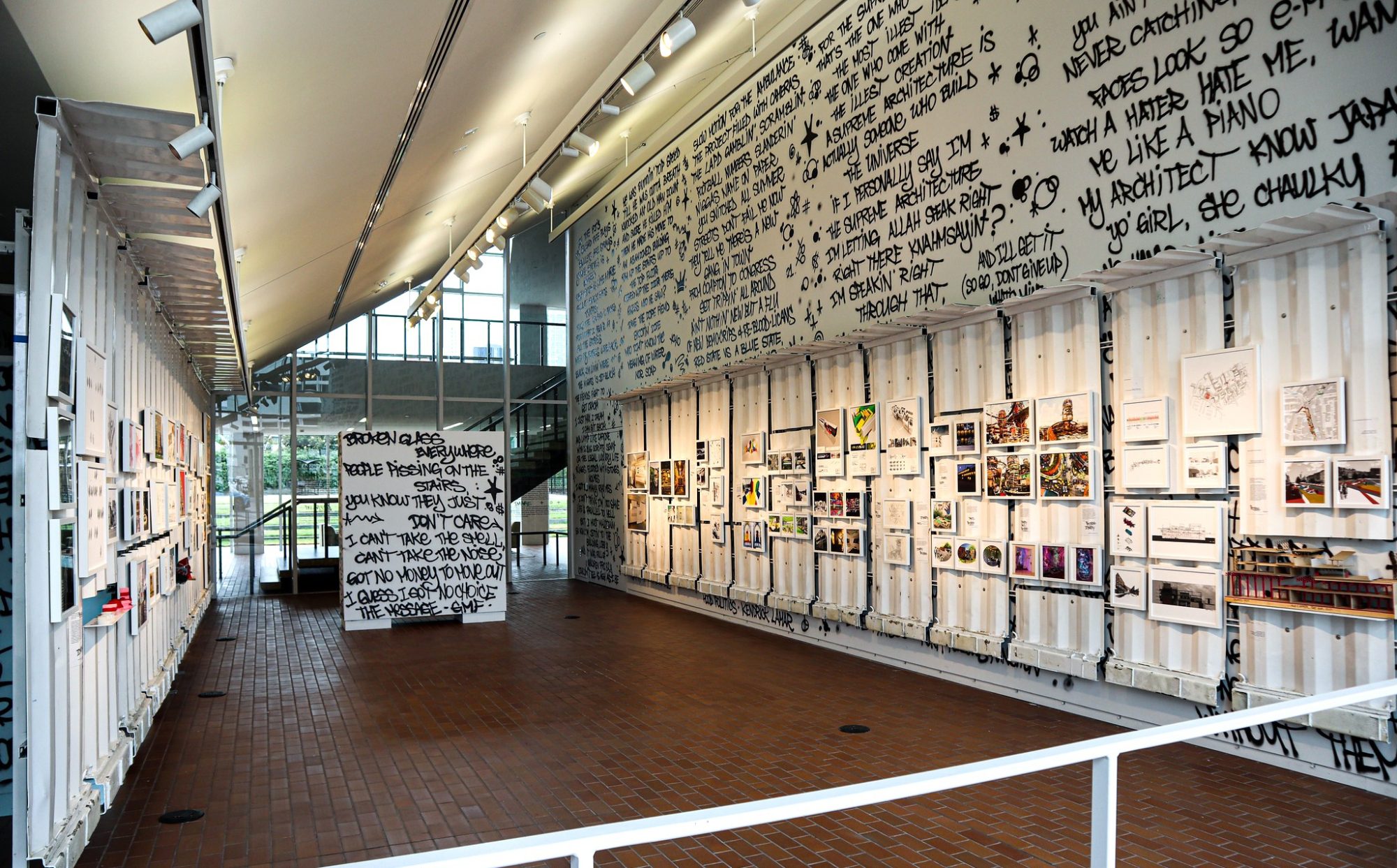

“Walk through The Dubois Center at UNC Charlotte Center City and you’ll see rap lyrics from Nas, Slick Rick and Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s hit song ‘The Message’ splashed in graffiti on the walls,” wrote Gordon Rago recently in the Charlotte Observer. “Framed photos hang on fragments of a shipping container, showing concepts of projects that could be interpreted as hip-hop architecture. There are 3-D models, devoid of color, showing distorted, off-grid structures that shift your thinking about what a traditional building looks like.”

This nontraditional exhibition in The Dubois Center’s Projective Eye Gallery is Close to the Edge: The Birth of Hip-Hop Architecture, a show curated by Master of Urban Design Director Sekou Cooke, on view through July 15. The exhibition celebrates the work of practitioners, academics, and students at the center of an emerging architectural revolution.

“I want people to see that there is a different way of approaching architecture than they might have been exposed to in the past––one that is rooted in the cultural expressions of peoples often omitted from most conversations about architecture,” Cooke said recently. Cooke came to UNC Charlotte last fall from Syracuse University, where he was a professor in the School of Architecture. He is the author of the monograph, Hip-Hop Architecture, published in spring 2021.

Hip-hop was established by the Black and Latino youth of New York’s South Bronx neighborhood in the early 1970s. Over the last five decades, hip-hop’s primary means of expression—deejaying, emceeing, b-boying, and graffiti—have become globally recognized creative practices in their own right, and each has significantly impacted the urban built environment. Hip-Hop Architecture translates these elements of hip-hop culture into spaces, buildings, and environments.

Close to the Edge: The Birth of Hip-Hop Architecture includes work by 25 participants representing seven countries, with projects ranging across a variety of media and forms of expression. The exhibition is organized using three primary characteristics: hip-hop identity